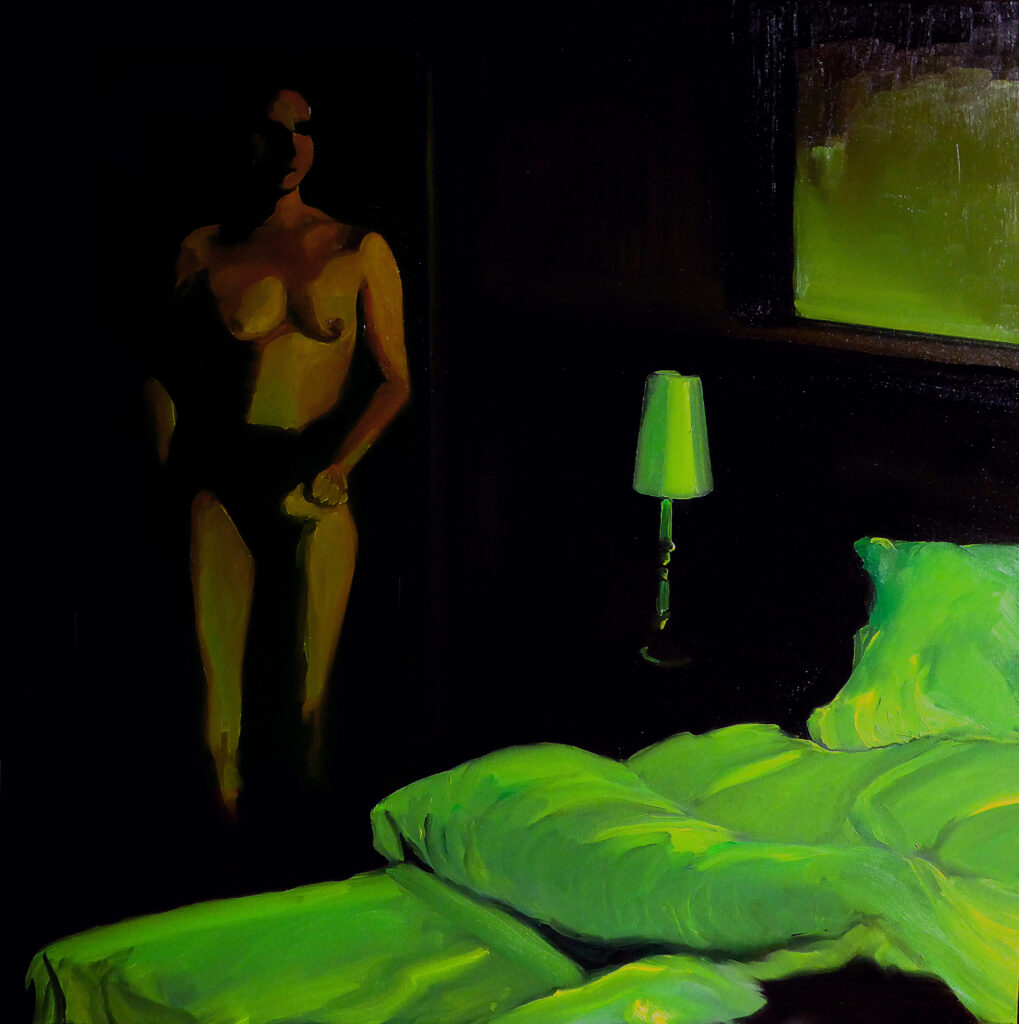

What is brewing

huile sur toile 100×100 cm

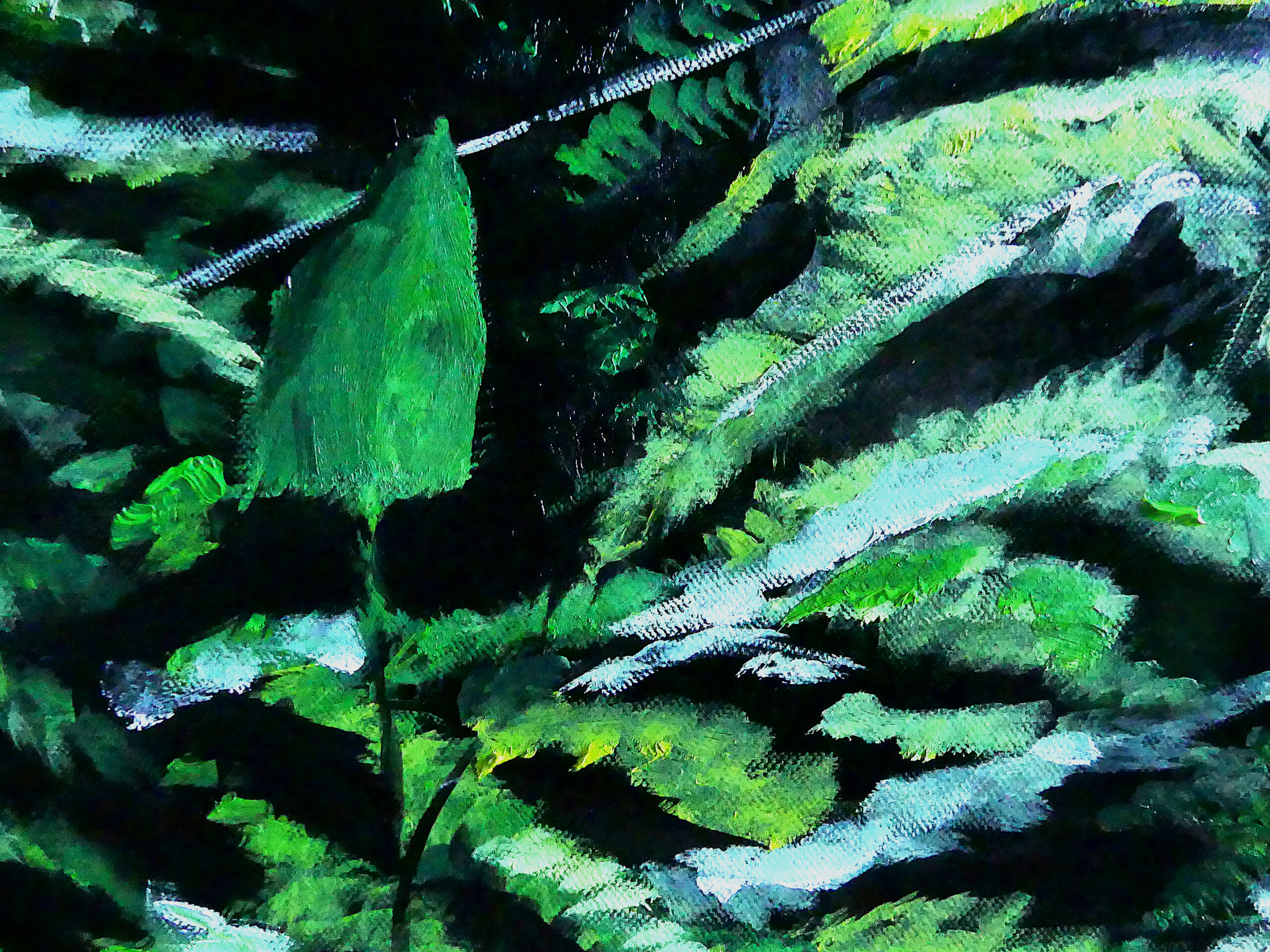

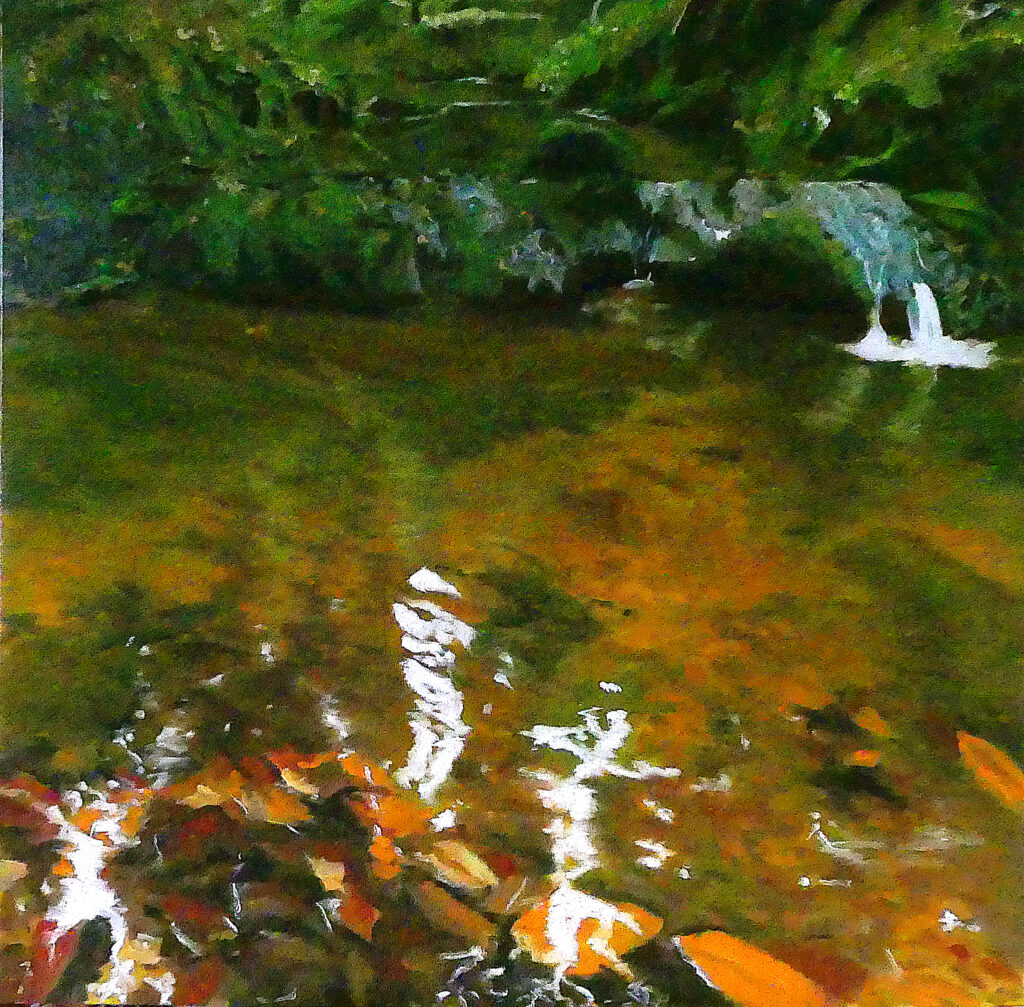

I remember an incursion into the equatorial forest of Congo thirty years ago. We were in Mbandaka with a friend, waiting in vain for the floating city boat that was supposed to take us back to Kinshasa. To pass the time, we decided to visit the forest, the territory of the Pygmies. When they venture into the city, they are treated by the Bantus as subhumans. We asked the taxi driver (a Bantu) to randomly take us to the end of one of the paths that delve into Pygmy territory. As we progressed, the driver became more and more nervous. The path ended in a Pygmy village where I asked the Chief to show us around in exchange for a gift for the village… Off we went, two men with machetes clearing the way, and two men with machetes bringing up the rear behind the chief, the sorcerer, my friend, and me, along with the increasingly nervous driver in the stifling humidity of the primary forest. The chief introduced us to the dead of the village, whose spirits rested in tiny colorful houses scattered under the trees. Then we ventured into a kind of swamp between enormous roots, infinite trunks, and cries of animals unknown to us. But after about twenty minutes of walking, screams erupted from behind. Our driver was gesticulating wildly as if shaken by electric shocks, while the two Pygmies at the end of the procession seemed determined to cut him into pieces. Our driver, so disdainful towards them in the city, was here gripped by panic, dominated by the spirits complicit with the men of the forest. We had to negotiate his safety with the Chief and shorten our visit to remove our Bantu taxi from the magic of the forests. For everything signals in the forest. The shapes, the tracks, the sounds, the cries, the cracklings, the rustlings, the changing patterns of light and shadow, the strange contrasts of colors… Anyone who has slept alone in the forest knows these fanfares of signals. In our land, the Druids drew secrets of divination from them.